Cape Town energy and

climate change guru,Sarah Ward, is not only passionate about energy, but she

is a full-on bundle of energy in her own right. From her roots in

groundbreaking non-profit environmental organisations, to her involvement in

the development of The Green Building at Westlake in Cape Town. Andy Mason

spoke to her about her vision for the Cape Town of the future, and the

prospects for low-carbon urban development on the African continent.

The city of the future – low-carbon, low-waste and planet-friendly with comprehensive recycling, diverse energy sources and decentralised human-scale environments where pedestrians predominate – is not a mere idealistic dream. According to Ward, it is a completely realistic and achievable goal.

“By when?” I ask.

“Sometime between tomorrow and 2030,” she answers.

Here is a person for whom the problems of the present and the challenges of the

future are nothing less than great opportunities to make South Africa’s

loveliest city the most energy-efficient, planet-friendly urban centre on the

continent.

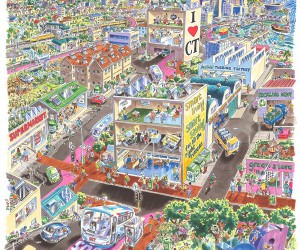

A level of ambition that may seem overblown to the normal person is simply business as usual for Ward.When I ask her to describe what a low-carbon city may look like, she pulls out a poster depicting an idealised future Cape Town.With infectious enthusiasm, Ward begins to elaborate on the image. With its green buildings built with recycled materials, insulated against the Cape Town weather and powered by clean energy. Of course, once we get down to the nitty-gritty, it is not quite as simple as all that. “There’s no silver bullet that is going to fix the problems in every area,” cautions Ward. “Solutions will have to be developed locally, in collaboration with local communities.”

So if there is no silver bullet, is there an overarching concept that holds the plan together? “Resource efficiency”, she replies, “needs to be a top priority. Resources are scarce. And so we have to treat them like gold.”

The ideologically driven

geography of the apartheid city has to be unravelled and reconfigured. This,

quite obviously, is not something that is going to be achieved in a day. It is

a slow, iterative process that is beset by a myriad of obstacles along the way.For example, the sustainable, low-carbon city needs to

have a highly efficient integrated system of transport infrastructure. If a

city’s rail system is safe, cheap and runs like clockwork, people will use it.

But South African cities do not have control over the rail system, which is

owned and run nationally by Metrorail – making the integration of transport

modes more difficult.

Solutions to these problems are presently being worked on by cities and the national government and Cape Town’s new BRT system demonstrates the benefits of locally driven planning and implementation, but is not without its problems.

"Large, long-term projects need longer term funding mechanisms, and this is often not how government finance systems work,” says Ward. “However, as sustainability issues become stronger drivers of urban economies, this will need to change”. Cape Town’s energy future looks good to me, as I succumb to the compelling logic of Ward’s vision. But what of the rest of the continent?

“The

problem”, she says, “is that not many African countries have fully functional

local governments and national governments tend to hold these responsibilities.

So, is it even possible to speak of a low-carbon future for the African

continent? Ward replies: “Africa is already low-carbon! Most people in African

cities use very little energy, and in fact need access to more and better energy sources.

Does Ward think Cape Town is potentially a world leader in low-carbon urban development? Indeed she does. “Cape Town is better organised than many other cities in the developing world,” she says. “When it comes to building energy efficiency, we are a leader – not only in Africa, but also in comparison to many cities in the developed world.”

Andy Mason